cosmos.wikisort.org - Spacecraft

Gemini 1 was the first mission in NASA's Gemini program.[2] An uncrewed test flight of the Gemini spacecraft, its main objectives were to test the structural integrity of the new spacecraft and modified Titan II launch vehicle. It was also the first test of the new tracking and communication systems for the Gemini program and provided training for the ground support crews for the first crewed missions.[3]

Launch of Gemini 1 | |

| Mission type | Test flight |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1964-018A |

| SATCAT no. | 782 |

| Mission duration | 4 hours 50 minutes |

| Distance travelled | 1,733,541 miles (2,789,864 km) |

| Orbits completed | 63 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Gemini SC1 |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell |

| Launch mass | 7,026 pounds (3,187 kg) (11,400 pounds (5,170 kg) with 2nd stage) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | April 8, 1964, 16:01:01.69 UTC |

| Rocket | Titan II GLV, s/n 62-12556 |

| Launch site | Cape Kennedy LC-19 |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Uncontrolled reentry |

| Decay date | April 12, 1964, 15:00:00 UTC |

| Landing site | Middle of South Atlantic Ocean |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 84 nautical miles (155 km) |

| Apogee altitude | 146 nautical miles (271 km) |

| Inclination | 32.5 degrees |

| Period | 88.76 minutes |

| Epoch | April 10, 1964[1] |

Project Gemini | |

Originally scheduled for launch in December 1963, difficulties in the development of both the spacecraft and its booster caused four months of delay. Gemini 1 was launched from Launch Complex 19 at Cape Kennedy (now Canaveral), Florida on April 8, 1964. The spacecraft stayed attached to the second stage of the rocket. The mission lasted for three orbits while test data were taken, but the spacecraft stayed in space for almost 64 orbits until its orbit decayed due to atmospheric drag. The spacecraft was not intended to be recovered, and holes were drilled through its heat shield to ensure it would not survive re-entry.

Background

Project Gemini was conceived as a bridge between America's single-seat Project Mercury and the three-seat Project Apollo. With a design largely extrapolated from its predecessor,[4]: 71 the Gemini spacecraft would allow two astronauts to conduct the maneuvers inherent in Apollo's lunar mission: rendezvous, docking, and changing of orbit. Moreover, Gemini would support astronauts in space for extended flights, approximating the expected length of the Apollo missions.[4]: 55–74

Its two-person capacity and greater capabilities meant that Gemini would be a substantially heavier spacecraft than Mercury had been — too heavy to be lofted into orbit by Mercury's Atlas rocket. A replacement was needed. The newly developed Titan II ICBM (which had also been tapped by the Air Force for its X-20 spaceplane project) was an attractive replacement. It had a thrust some two and a half times that of the Atlas, a far simpler mechanical construction, and the ability to store propellants indefinitely. Moreover, the Titan II's propellants mixed less violently than those of Atlas meaning a booster explosion, should it happen, would be less violent. This made obsolete the heavy escape tower used in the Mercury program; instead, ejection seats could be used.[4]: 41–42

The primary goal of the first Gemini mission was to flight test the modified Titan II launch vehicle and the basic structural soundness of the Gemini capsule under launch and orbital conditions. Consequently, the first Gemini capsule could be a largely boilerplate structure.[4]: 181 Secondary goals of the mission included testing the remote guidance systems, the Titan's redundancy systems, and evaluation of the Gemini-Titan malfunction detection system.[5]

Pre-flight

Gemini Spacecraft Number 1 was built specifically for the uncrewed mission. Most internal systems were replaced with dummies and ballast approximating the weight and balance of the crewed spacecraft. In place of the crew couches, two pallets of instruments were installed for the relaying via telemetry of the pressure, vibration, acceleration, temperature, and structural loads experienced during the short flight. A spacecraft heat shield was installed, but four large holes were drilled in it to ensure Gemini 1 was destroyed during reentry.[4]: 181

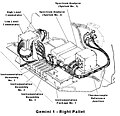

- Gemini 1 Instrument Pallets

- Gemini 1 Right Pallet

- Gemini 1 Left Pallet

Even with the simplified systems, this first Gemini encountered several weeks of delay in testing. Nevertheless, it was not the spacecraft that caused the launch date, originally planned for December 1963, to slip. Rather, it was the testing and man-rating of the Titan II launch vehicle. Assembled on May 21, 1963, the first Titan-Gemini launch vehicle required comprehensive testing and retesting, and it was not until October that it was ready for transport to the launch site — where considerable preparation still had to be done.[4]: 185 Moreover, there was concern that the Titan II produced too much vertical oscillation (pogo) to be usable at all, and consideration was given to using the Saturn I rocket instead, at least for the first missions. However, on November 1, 1963, the Air Force flew a Titan II rocket with standpipes in its oxidizer lines and mechanical accumulators in its fuel lines, which suppressed the pogo effect.[6]

Inefficient project management threatened to further delay the first Gemini launch, which by November had already been pushed back to February 28, 1964. Gemini Manager Charles Mathews united the several disparate teams into a single Gemini Launch Vehicle Coordination Committee with clearly defined management and communication channels.[4]: 188 This measure ensured that no more time would be lost due to uncertain authority, duplicated effort, or conflicting decisions. Still, issues that arose during testing caused the launch date to slip further.[4]: 189 The Titan II booster was not ready for final readiness testing until March 3, 1964, the same day that Gemini Spacecraft Number 1 arrived at the launch complex for mating with its booster.[4]: 190 Faulty test equipment caused a further delay of two weeks. By late March, all serious hurdles cleared, Gemini 1's launch date was set for April 7.[4]: 195 The resolution of a failure in the secondary autopilot caused one last day of delay. Finally, by noon of the seventh, Gemini 1's Mission Review Board determined unanimously that all systems were cleared for flight.[4]: 197

Mission and Results

After a flawless countdown, Gemini 1's Titan II booster lifted off from Cape Kennedy's (now Canaveral) Launch Complex 19[4]: 194 at 11:00:01 EDT, April 8, 1964.[4]: 197 The first stage was jettisoned after two and a half minutes with the rocket 35 nautical miles (64 km) high and 49 nautical miles (91 km) downrange. At that moment, there was an unexpected three-second loss of signal from the craft. It was later determined that this brief communications blackout was caused by charged ions from the separation and startup of the second stage, similar to the blackout during spacecraft reentry. All subsequent Gemini flights would have the same brief blackout.[7]

The spacecraft achieved orbit five and a half minutes after launch. The launch vehicle had imparted an excess 7 meters (24 feet) per second of velocity to the Gemini 1, placing the spacecraft into an orbit with an apogee of 170 nautical miles (320 km) instead of the planned 161 nautical miles (299 km). This lengthened Gemini 1's lifespan from the planned three and a half days to four.[4]: 199

The formal mission of Gemini 1 was over long before that. Its battery had only been designed to last a single orbit,[8] and only the first three orbits — lasting four hours and 50 minutes — were part of the flight plan. Gemini 1 and its attached second stage were tracked by the Manned Space Flight Network until they reentered over the South Atlantic, midway between South America and Africa, on April 12, 1964, during their 64th orbit.[4]: 199

As a result of the successful flight, the Titan II was considered "man-rated" (safe for use in human spaceflight).[4]: 200 Man-rating the Gemini capsule itself would not be accomplished until the launch of Gemini 2 nine months later, on January 19, 1965.[4]: 209

The Gemini 1 mission was supported by 5,176 United States Department of Defense personnel, as well as eleven aircraft and three ships provided by the Department of Defense.[4]: Appendix G-299

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- "Gemini 1". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- "Gemini 1". Gunter's Space Page. December 11, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- Hacker, Barton C.; Grimwood, James M. (February 2003) [First published 1977]. "Table of Contents". On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 9781493775910. NASA SP-4203. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "First Successful Gemini Mission Points to Manned Flight in 1964". Aviation Week and Space Technology. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing Company. April 13, 1964. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- "Why Did NASA Choose an Untested Missile to Launch Gemini?". Popular Science. January 17, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- Chris Kraft, Flight, p. 203.

- "Gemini Flight Readied". Aviation Week and Space Technology. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing Company. April 6, 1964. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

External links

- On The Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini

- Gemini Program Mission Report for Gemini-Titan 1 (GT-1) from the NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

На других языках

- [en] Gemini 1

[es] Gemini 1

Gemini 1 fue una misión no tripulada del programa Gemini en 1964. Esta misión fue la primera prueba de la cápsula Gemini. Sus objetivos principales eran probar la integridad estructural de la nueva nave espacial y el modificado Titán II ICBM. Así como la primera prueba de los nuevos sistemas de rastreo y comunicación para el programa Gemini y el entrenamiento de los equipos para las primeras misiones tripuladas.[ru] Джемини-1

«Джемини-1» — первый испытательный полёт американского космического корабля «Джемини» в беспилотном режиме.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии