cosmos.wikisort.org - Spacecraft

Stardust was a 390-kilogram robotic space probe launched by NASA on 7 February 1999. Its primary mission was to collect dust samples from the coma of comet Wild 2, as well as samples of cosmic dust, and return them to Earth for analysis. It was the first sample return mission of its kind. En route to comet Wild 2, it also flew by and studied the asteroid 5535 Annefrank. The primary mission was successfully completed on 15 January 2006 when the sample return capsule returned to Earth.[9]

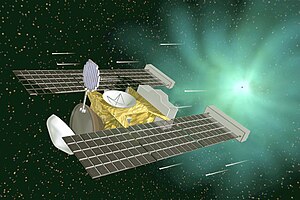

Artist's impression of Stardust at comet Wild 2 | |||||||||||||

| Names | Discovery 4 Stardust-NExT | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Sample return | ||||||||||||

| Operator | NASA / JPL | ||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 1999-003A | ||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 25618 | ||||||||||||

| Website | stardust stardustnext | ||||||||||||

| Mission duration | Stardust: 6 years, 11 months, 7 days NExT: 4 years, 2 months, 7 days Total: 9 years, 1 month, 17 days | ||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||

| Bus | SpaceProbe[1] | ||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin University of Washington | ||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 390.599 kg (861 lb)[2] | ||||||||||||

| Dry mass | 305.397 kg (673 lb)[2] | ||||||||||||

| Dimensions | Bus: 1.71 × 0.66 × 0.66 m[1] (5.6 × 2.16 × 2.16 ft) | ||||||||||||

| Power | 330 W (Solar array / NiH2 batteries) | ||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||

| Launch date | 7 February 1999, 21:04:15.238 UTC[3] | ||||||||||||

| Rocket | Delta II 7426-9.5 #266 | ||||||||||||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17 | ||||||||||||

| Contractor | Lockheed Martin Space Systems | ||||||||||||

| End of mission | |||||||||||||

| Disposal | Decommissioned | ||||||||||||

| Deactivated | Spacecraft: 24 March 2011, 23:33 UTC[4] | ||||||||||||

| Landing date | Capsule: 15 January 2006, 10:12 UTC[5] | ||||||||||||

| Landing site | Utah Test and Training Range 40°21.9′N 113°31.25′W | ||||||||||||

| Flyby of Earth | |||||||||||||

| Closest approach | 15 January 2001, 11:14:28 UTC | ||||||||||||

| Distance | 6,008 km (3,733 mi) | ||||||||||||

| Flyby of asteroid 5535 Annefrank | |||||||||||||

| Closest approach | 2 November 2002, 04:50:20 UTC[6] | ||||||||||||

| Distance | 3,079 km (1,913 mi)[6] | ||||||||||||

| Flyby of periodic comet Wild 2 | |||||||||||||

| Closest approach | 2 January 2004, 19:21:28 UTC[6] | ||||||||||||

| Distance | 237 km (147 mi)[6] | ||||||||||||

| Flyby of Earth (Sample return) | |||||||||||||

| Closest approach | 15 January 2006 | ||||||||||||

| Flyby of Earth | |||||||||||||

| Closest approach | 14 January 2009, 12:33 UTC | ||||||||||||

| Distance | 9,157 km (5,690 mi) | ||||||||||||

| Flyby of comet Tempel 1 | |||||||||||||

| Closest approach | 15 February 2011, 04:39:10 UTC[7] | ||||||||||||

| Distance | 181 km (112 mi)[8] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Discovery program | |||||||||||||

A mission extension, codenamed NExT, culminated in February 2011 with Stardust intercepting comet Tempel 1, a small Solar System body previously visited by Deep Impact in 2005. Stardust ceased operations in March 2011.

On 14 August 2014, scientists announced the identification of possible interstellar dust particles from the Stardust capsule returned to Earth in 2006.[10][11][12][13]

Mission background

History

Beginning in the 1980s, scientists began seeking a dedicated mission to study a comet. During the early 1990s, several missions to study comet Halley became the first successful missions to return close-up data. However, the US cometary mission, Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby, was canceled for budgetary reasons. In the mid-1990s, further support was given to a cheaper, Discovery-class mission that would study comet Wild 2 in 2004.[1]

Stardust was competitively selected in the fall of 1995 as a NASA Discovery Program mission of low-cost with highly focused science goals.[1]: 5 Construction of Stardust began in 1996, and was subject to the maximum contamination restriction, level 5 planetary protection. However, the risk of interplanetary contamination by alien life was judged low,[14] as particle impacts at over 1,000 miles per hour, even into aerogel, were believed to be terminal for any known microorganism.[1]: 22–23

Comet Wild 2 was selected as the primary target of the mission for the rare chance to observe a long-period comet that has ventured close to the Sun. The comet has since become a short period comet after an event in 1974, where the orbit of Wild 2 was affected by the gravitational pull of Jupiter, moving the orbit inward, closer to the Sun. In planning the mission, it was expected that most of the original material from which the comet formed would still be preserved.[1]: 5

The primary science objectives of the mission included:[6]

- Providing a flyby of a comet of interest (Wild 2) at a sufficiently low velocity (less than 6.5 km/s) such that non-destructive capture of comet dust is possible using an aerogel collector.

- Facilitating the intercept of significant numbers of interstellar dust particles using the same collection medium, also at as low a velocity as possible.

- Returning as many high-resolution images of the comet coma and nucleus as possible, subject to the cost constraints of the mission.

The spacecraft was designed, built and operated by Lockheed Martin Astronautics as a Discovery-class mission in Denver, Colorado. JPL provided mission management for the NASA division for mission operations. The principal investigator of the mission was Dr. Donald Brownlee from the University of Washington.[1]: 5

Spacecraft design

The spacecraft bus measured 1.7 meters (5 ft 7 in) in length, and 0.66 meters (2 ft 2 in) in width, a design adapted from the SpaceProbe deep space bus developed by Lockheed Martin Astronautics. The bus was primarily constructed with graphite fiber panels with an aluminum honeycomb support structure underneath; the entire spacecraft was covered with polycyanate, Kapton sheeting for further protection. To maintain low costs, the spacecraft incorporated many designs and technologies used in past missions or previously developed for future missions by the Small Spacecraft Technologies Initiative (SSTI). The spacecraft featured five scientific instruments to collect data, including the Stardust Sample Collection tray, which was brought back to Earth for analysis.[15]

Attitude control and propulsion

The spacecraft was three-axis stabilized with eight 4.41 N hydrazine monopropellant thrusters, and eight 1-Newton thrusters to maintain attitude control (orientation); necessary minor propulsion maneuvers were performed by these thrusters as well. The spacecraft was launched with 80 kilograms of propellant. Information for spacecraft positioning was provided by a star camera using FSW to determine attitude (stellar compass), an inertial measurement unit, and two sun sensors.[1]: 30–31 [15]

Communications

For communicating with the Deep Space Network, the spacecraft transmitted data across the X-band using a 0.6-meter (2 ft 0 in) parabolic high-gain antenna, medium-gain antenna (MGA) and low-gain antennas (LGA) depending on mission phase, and a 15-watt transponder design originally intended for the Cassini spacecraft.[1]: 32 [15]

Power

The probe was powered by two solar arrays, providing an average of 330 watts of power. The arrays also included Whipple shields to protect the delicate surfaces from the potentially damaging cometary dust while the spacecraft was in the coma of Wild 2. The solar array design was derived primarily from the Small Spacecraft Technology Initiative (SSTI) spacecraft development guidelines. The arrays provided a unique method of switching strings from series to parallel depending on the distance from the Sun. A single nickel–hydrogen (NiH2) battery was also included to provide the spacecraft with power when the solar arrays received too little sunlight.[1]: 31 [15]

Computer

The computer on the spacecraft operated using a radiation-hardened RAD6000 32-bit processor card. For storing data when the spacecraft was unable to communicate with Earth, the processor card was able to store 128 megabytes, 20% of which was occupied by the flight system software. The system software is a form of VxWorks, an embedded operating system developed by Wind River Systems.[1]: 31 [15]

Scientific instruments

| Navigation Camera (NC) | |||

|

The camera is intended for targeting comet Wild 2 during the flyby of the nucleus. It captures black and white images through a filter wheel making it possible to assemble color images and detect certain gas and dust emissions in the coma. It also captures images at various phase angles, making it possible to create a three-dimensional model of a target to better understand the origin, morphology, and mineralogical inhomogeneities on the surface of the nucleus. The camera utilizes the optical assembly from the Voyager Wide Angle Camera. It is additionally fitted with a scanning mirror to vary the viewing angle and avoid potentially damaging particles. For environmental testing and verification of the NAVCAM the only remaining Voyager spare camera assembly was used as a collimator for testing of the primary imaging optics. A target at the focal point of the spare was imaged through the optical path of the NAVCAM for verification.[16][17]

| ||

| Cometary and Interstellar Dust Analyzer (CIDA) | |||

The dust analyzer is a mass spectrometer able to provide real-time detection and analysis of certain compounds and elements. Particles enter the instrument after colliding with a silver impact plate and traveling down a tube to the detector. The detector is then able to detect the mass of separate ions by measuring the time taken for each ion to enter and travel through the instrument. Identical instruments were also included on Giotto and Vega 1 and 2.[18][19]

| |||

| Dust Flux Monitor Instrument (DFMI) | |||

|

Located on the Whipple shield at the front of the spacecraft, the sensor unit provides data regarding the flux and size distribution of particles in the environment around Wild 2. It records data by generating electric pulses as a special polarized plastic (PVDF) sensor is struck by high energy particles as small as a few micrometers.[20][21]

| ||

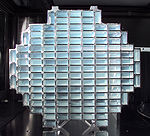

| Stardust Sample Collection (SSC) | |||

|

The particle collector uses aerogel, a low-density, inert, microporous, silica-based substance, to capture dust grains as the spacecraft passes through the coma of Wild 2. After sample collection was complete, the collector receded into the Sample Return Capsule for entering the Earth's atmosphere. The capsule with encased samples would be retrieved from Earth's surface and studied.[22][23]

| ||

| Dynamic Science Experiment (DSE) | |||

The experiment will primarily utilize the X band telecommunications system to conduct radio science on Wild 2, to determine the mass of the comet; secondarily the inertial measurement unit is utilized to estimate the impact of large particle collisions on the spacecraft.[24][25]

| |||

Sample collection

Comet and interstellar particles are collected in ultra low density aerogel. The tennis racket-sized collector tray contained ninety blocks of aerogel, providing more than 1,000 square centimeters of surface area to capture cometary and interstellar dust grains.

To collect the particles without damaging them, a silicon-based solid with a porous, sponge-like structure is used in which 99.8 percent of the volume is empty space. Aerogel has 1⁄1000 the density of glass, another silicon-based solid to which it may be compared. When a particle hits the aerogel, it becomes buried in the material, creating a long track, up to 200 times the length of the grain. The aerogel was packed in an aluminium grid and fitted into a Sample Return Capsule (SRC), which was to be released from the spacecraft as it passed Earth in 2006.

To analyze the aerogel for interstellar dust, one million photographs will be needed to image the entirety of the sampled grains. The images will be distributed to home computer users to aid in the study of the data using a program titled, Stardust@home. In April 2014, NASA reported they had recovered seven particles of interstellar dust from the aerogel.[26]

Stardust microchip

Stardust was launched carrying two sets of identical pairs of square 10.16-centimeter (4 in) silicon wafers. Each pair featured engravings of well over one million names of people who participated in the public outreach program by filling out internet forms available in late 1997 and mid-1998. One pair of the microchips was positioned on the spacecraft and the other was attached to the sample return capsule.[1]: 24

Mission profile

Launch and trajectory

Stardust · 81P/Wild · Earth · 5535 Annefrank · Tempel 1

Stardust was launched at 21:04:15 UTC on 7 February 1999, by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from Space Launch Complex 17A at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, aboard a Delta II 7426 launch vehicle. The complete burn sequence lasted for 27 minutes bringing the spacecraft into a heliocentric orbit that would bring the spacecraft around the Sun and past Earth for a gravity assist maneuver in 2001, to reach asteroid 5535 Annefrank in 2002 and comet Wild 2 in 2004 at a low flyby velocity of 6.1 km/s. In 2004, the spacecraft performed a course correction that would allow it to pass by Earth a second time in 2006, to release the Sample Return Capsule for a landing in Utah in the Bonneville Salt Flats.[1]: 14–22 [6]

During the second encounter with Earth, the Sample Return Capsule was released on Jan 15, 2006.[6] Immediately afterwards, Stardust was put into a "divert maneuver" to avoid entering the atmosphere alongside the capsule. Under twenty kilograms of propellant remained onboard after the maneuver.[6] On 29 January 2006, the spacecraft was put in hibernation mode with only the solar panels and receiver active, in a 3-year heliocentric orbit that would return it to Earth vicinity on 14 January 2009.[6][27]

A subsequent mission extension was approved on 3 July 2007, to bring the spacecraft back to full operation for a flyby of comet Tempel 1 in 2011. The mission extension was the first to revisit a small Solar System body and used the remaining propellant, signaling the end of the useful life for the spacecraft.[28]

| Timeline of travel[6][29] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Encounter with Annefrank

At 04:50:20 UTC on 2 November 2002, Stardust encountered asteroid 5535 Annefrank from a distance of 3,079 km (1,913 mi).[6] The solar phase angle ranged from 130 degrees to 47 degrees during the period of observations. This encounter was used primarily as an engineering test of the spacecraft and ground operations in preparation for the encounter with comet Wild 2 in 2003.[6]

Encounter with Wild 2

At 19:21:28 UTC, on 2 January 2004, Stardust encountered Comet Wild 2[33] on the sunward side with a relative velocity of 6.1 km/s at a distance of 237 km (147 mi).[6] The original encounter distance was planned to be 150 km (93 mi), but this was changed after a safety review board increased the closest approach distance to minimize the potential for catastrophic dust collisions.[6]

The relative velocity between the comet and the spacecraft was such that the comet actually overtook the spacecraft from behind as they traveled around the Sun. During the encounter, the spacecraft was on the Sunlit side of the nucleus, approaching at a solar phase angle of 70 degrees, reaching a minimum angle of 3 degrees near closest approach and departing at a phase angle of 110 degrees.[6] The AutoNav software was used during the flyby.: 11

During the flyby the spacecraft deployed the Sample Collection plate to collect dust grain samples from the coma, and took detailed pictures of the icy nucleus.[35]

New Exploration of Tempel 1 (NExT)

On 19 March 2006, Stardust scientists announced that they were considering the possibility of redirecting the spacecraft on a secondary mission to image Comet Tempel 1. The comet was previously the target of the Deep Impact mission in 2005, sending an impactor into the surface. The possibility of this extension could be vital for gathering images of the impact crater which Deep Impact was unsuccessful in capturing due to dust from the impact obscuring the surface.

On 3 July 2007 the mission extension was approved and renamed New Exploration of Tempel 1 (NExT). This investigation would provide the first look at the changes to a comet nucleus produced after a close approach to the Sun. NExT also would extend the mapping of Tempel 1, making it the most mapped comet nucleus to date. This mapping would help address the major questions of comet nucleus geology. The flyby mission was expected to consume almost all of the remaining fuel, signaling the end of the operability of the spacecraft.[28] The AutoNav software (for autonomous navigation) would control the spacecraft for the 30 minutes prior to encounter.[36]

The mission objectives included the following:[36]

Primary objectives

- Extend the current understanding of the processes that affect the surfaces of comet nuclei by documenting the changes that have occurred on comet Tempel 1 between two successive perihelion passages, or orbits around the Sun.

- Extend the geologic mapping of the nucleus of Tempel 1 to elucidate the extent and nature of layering, and help refine models of the formation and structure of comet nuclei.

- Extend the study of smooth flow deposits, active areas and known exposure of water ice.

Secondary objectives

- Potentially image and characterize the crater produced by Deep Impact in July 2005, to better understand the structure and mechanical properties of cometary nuclei and elucidate crater formation processes on them.

- Measure the density and mass distribution of dust particles within the coma using the Dust Flux Monitor Instrument.

- Analyze the composition of dust particles within the coma using the Comet and Interstellar Dust Analyzer instrument.

Encounter with Tempel 1

At 04:39:10 UTC on 15 February 2011, Stardust-NExT encountered Tempel 1 from a distance of 181 km (112 mi).[7][8] An estimated 72 images were acquired during the encounter. These showed changes in the terrain and revealed portions of the comet never seen by Deep Impact.[37] The impact site from Deep Impact was also observed, though it was barely visible due to material settling back into the crater.[38]

End of extended mission

On 24 March 2011 at approximately 23:00 UTC, Stardust conducted a burn to consume its remaining fuel.[32] The spacecraft had little fuel left and scientists hoped the data collected would help in the development of a more accurate system for estimating fuel levels on spacecraft. After the data had been collected, no further antenna aiming was possible and the transmitter was switched off. The spacecraft sent an acknowledgement from approximately 312 million km (194 million mi) away in space.[4]

Sample return

On 15 January 2006, at 05:57 UTC, the Sample Return Capsule successfully separated from Stardust. The SRC re-entered the Earth's atmosphere at 09:57 UTC,[39] with a velocity of 12.9 km/s, the fastest reentry speed into Earth's atmosphere ever achieved by a human-made object.[40] The capsule followed a drastic reentry profile, going from a velocity of Mach 36 to subsonic speed within 110 seconds.[41][failed verification] Peak deceleration was 34 g,[42] encountered 40 seconds into the reentry at an altitude of 55 km over Spring Creek, Nevada.[41] The phenolic-impregnated carbon ablator (PICA) heat shield, produced by Fiber Materials Inc., reached a temperature of more than 2,900 °C during this steep reentry.[43] The capsule then parachuted to the ground, finally landing at 10:12 UTC at the Utah Test and Training Range, near the U.S. Army Dugway Proving Ground.[5][44] The capsule was then transported by military aircraft from Utah to Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, Texas, then transferred by road in an unannounced convoy to the Planetary Materials Curatorial facility at Johnson Space Center in Houston to begin analysis.[6][45]

Sample processing

The sample container was taken to a clean room with a cleanliness factor 100 times that of a hospital operating room to ensure the interstellar and comet dust was not contaminated.[46] Preliminary estimations suggested at least a million microscopic specks of dust were embedded in the aerogel collector. Ten particles were found to be at least 100 micrometers (0.1 mm) and the largest approximately 1,000 micrometers (1 mm). An estimated 45 interstellar dust impacts were also found on the sample collector, which resided on the back side of the cometary dust collector. Dust grains are being observed and analyzed by a volunteer team through the citizen science project, Stardust@Home.

The combined mass of the harvested sample was approximately 1 mg.[47]

In December 2006, seven papers were published in the scientific journal Science, discussing initial details of the sample analysis. Among the findings are: a wide range of organic compounds, including two that contain biologically usable nitrogen; indigenous aliphatic hydrocarbons with longer chain lengths than those observed in the diffuse interstellar medium; abundant amorphous silicates in addition to crystalline silicates such as olivine and pyroxene, proving consistency with the mixing of Solar System and interstellar matter, previously deduced spectroscopically from ground observations;[48] hydrous silicates and carbonate minerals were found to be absent, suggesting a lack of aqueous processing of the cometary dust; limited pure carbon (CHON)[clarification needed] was also found in the samples returned; methylamine and ethylamine was found in the aerogel but was not associated with specific particles.

In 2010, Dr. Andrew Westphal announced that Stardust@home volunteer Bruce Hudson found a track (labeled "I1043,1,30") among the many images of the aerogel that may contain an interstellar dust grain.[49] The program allows for any volunteer discoveries to be recognized and named by the volunteer. Hudson named his discovery "Orion".[50]

In April 2011, scientists from the University of Arizona discovered evidence for the presence of liquid water in comet Wild 2. They have found iron and copper sulfide minerals that must have formed in the presence of water. The discovery shatters the existing paradigm that comets never get warm enough to melt their icy bulk.[51] In the spring of 2014, the recovery of particles of interstellar dust from the Discovery program's Stardust mission was announced.[52]

The Stardust samples are currently available for everyone to identify after completing the training at Berkeley webpage.[53]

Spacecraft location

The return capsule is currently located at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. It began exhibition there on 1 October 2008, the 50th anniversary of the establishment of NASA. The return capsule is displayed in sample collection mode, alongside a sample of the aerogel used to collect samples.[54]

Results

The comet samples show that the outer regions of the early Solar System were not isolated and were not a refuge where interstellar materials could commonly survive.[55] The data suggest that high-temperature inner Solar System material formed and was subsequently transferred to the Kuiper belt.[56]

- Glycine

In 2009 it was announced by NASA that scientists had identified one of the fundamental chemical building blocks of life in a comet for the first time: glycine, an amino acid, was detected in the material ejected from comet Wild 2 in 2004 and captured by the Stardust probe. Glycine has been detected in meteorites before and there are also observations in interstellar gas clouds, but the Stardust find is described as a first in cometary material. Isotope analysis indicates that the Late Heavy Bombardment included cometary impacts after the Earth coalesced but before life evolved.[57] Carl Pilcher, who leads NASA's Astrobiology Institute commented that "The discovery of glycine in a comet supports the idea that the fundamental building blocks of life are prevalent in space, and strengthens the argument that life in the universe may be common rather than rare."[58]

See also

- List of missions to comets

- Genesis, sample return from the solar wind

- Hayabusa, sample return from an asteroid

- List of uncrewed spacecraft by program

- Robotic spacecraft

- Space exploration

- Space probe

- Timeline of artificial satellites and space probes

- Timeline of first orbital launches by country

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

References

- "Stardust Launch" (PDF) (Press Kit). NASA. February 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2001.

- "Instrument Host Information: Stardust". Planetary Data System. NASA. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- "Stardust/NExT". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne (25 March 2011). "NASA Stardust Spacecraft Officially Ends Operations". NASA. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Muir, Hazel (15 January 2006). "Pinch of comet dust lands safely on Earth". New Scientist. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- "Mission Information: Stardust". Planetary Data System. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- "Mission Information: Next". Planetary Data System. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Greicius, Tony, ed. (14 February 2011). "NASA's Stardust Spacecraft Completes Comet Flyby". NASA. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Dolmetsch, Chris (15 January 2006). "NASA Spacecraft Returns With Comet Samples After 2.9 Bln Miles". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

- Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne; Jeffs, William (14 August 2014). "Stardust Discovers Potential Interstellar Space Particles". NASA. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Dunn, Marcia (14 August 2014). "Specks returned from space may be alien visitors". AP News. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Hand, Eric (14 August 2014). "Seven grains of interstellar dust reveal their secrets". Science. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Westphal, A. J.; Stroud, R. M.; Bechtel, H. A.; Brenker, F. E.; et al. (2014). "Evidence for interstellar origin of seven dust particles collected by the Stardust spacecraft" (PDF). Science. 345 (6198): 786–791. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..786W. doi:10.1126/science.1252496. hdl:2381/32470. PMID 25124433. S2CID 206556225.

- "Comets & The Question of Life". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 April 2001.

- "Stardust Flight System Description". NASA. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Newburn, R. L. Jr.; Bhaskaran, S.; Duxbury, T. C.; Fraschetti, G.; Radey, T.; Schwochert, M. (14 October 2003). "Stardust Imaging Camera". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (8116): 8116. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8116N. doi:10.1029/2003JE002081.

- "Imaging and Navigation Camera". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Kissel, J; Glasmachers, A.; Grün, E.; Henkel, H.; Höfner, H.; Haerendel, G.; von Hoerner, H.; Hornung, K.; Jessberger, E. K.; Krueger, F. R.; Möhlmann, D.; Greenberg, J. M.; Langevin, Y.; Silén, J.; Brownlee, D.; Clark, B. C.; Hanner, M. S.; Hoerz, F.; Sandford, S.; Sekanina, Z.; Tsou, P.; Utterback, N. G.; Zolensky, M. E.; Heiss, C. (2003). "Cometary and Interstellar Dust Analyzer for comet Wild 2". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (E10): 8114. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8114K. doi:10.1029/2003JE002091.

- "Cometary and Interstellar Dust Analyzer (CIDA)". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Tuzzolino, A. J. (2003). "Dust Flux Monitor Instrument for the Stardust mission to comet Wild 2". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (E10): 8115. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8115T. doi:10.1029/2003JE002086.

- "Dust Flux Monitor Instrument (DFMI)". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Tsou, P.; Brownlee, D. E.; Sandford, S. A.; Horz, F.; Zolensky, M. E. (2003). "Wild 2 and interstellar sample collection and Earth return". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (E10): 8113. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8113T. doi:10.1029/2003JE002109.

- "Stardust Sample Collection". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Anderson, John D.; Lau, Eunice L.; Bird, Michael K.; Clark, Benton C.; Giampieri, Giacomo; Patzold, Martin (2003). "Dynamic science on the Stardust mission". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (E10): 8117. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8117A. doi:10.1029/2003JE002092. S2CID 14492615.

- "Dynamic Science". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Seven samples from the solar system's birth".

- "Stardust Put In Hibernation Mode". Space.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2006.

- "Stardust/NExT – Five Things About NASA's Valentine's Day Comet". NASA. 10 February 2011.

- "Mission Timeline" (Press release). NASA. 14 February 2011.

- Savage, Donald; Heil, Martha J. (11 January 2001). "Stardust can see clearly now – just before Earth flyby". NASA / JPL. Archived from the original on 29 January 2001.

- Gasner, Steve; Sharmit, Khaled; Stella, Paul; Craig, Calvin; Mumaw, Susan (2003). The Stardust solar array. 3rd World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion. 11–18 May 2003. Osaka, Japan.

- "NASA's Stardust: Good to the Last Drop". NASA. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Williams, David E. (13 January 2006). "Spacecraft bringing comet dust back to Earth". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 January 2006.

- "STARDUST". Extrasolar-Planets. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009.

- "Stardust-NExT" (PDF) (Press Kit). NASA. February 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2011.

- "Image Gallery". Stardust-NExT - Exploring Comet Tempel 1. NASA. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011.

- Segal, Kimberly; Zarrella, John (16 February 2011). "Crater on comet 'partly healed itself'". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014.

- Farnham, T. L.; Semenov, B. (January 2010). "Stardust SRC Temperature Data V1.0". Planetary Data System. NASA: SDU–C–SRC–2–TEMPS–V1.0. Bibcode:2010PDSS.8187E....F.

- "Stardust Sample Return" (PDF) (Press Kit). NASA. January 2006.

- "Stardust Reentry Simulation". Evelyn Parker. 13 September 2013. Data in the simulation agrees with readings by the airborne observation team monitoring the reentry, available at Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Stardust Capsule Reentry". Stan Atamanchuk. 22 January 2011.

- ReVelle, D. O.; Edwards, W. N. (2007). "Stardust – An artificial, low-velocity "meteor" fall and recovery: 15 January 2006". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 42 (2): 271–299. Bibcode:2007M&PS...42..271R. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2007.tb00232.x.

- Winter, Michael W.; Trumble, Kerry A. (2010). "Spectroscopic Observation of the Stardust Re-Entry in the Near UV with SLIT: Deduction of Surface Temperatures and Plasma Radiation" (PDF). NASA.

- "NASA's Comet Tale Draws to a Successful Close in Utah Desert". NASA. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Oberg, James (18 January 2006). "Scientists overjoyed with comet samples". MSNBC. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Stardust's Cargo Comes to Houston under Veil of Secrecy". chron.com. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "Stardust Sample Collection". NASA.

- Van Boekel, R.; Min, M.; Leinert, Ch.; Waters, L. B. F. M.; Richichi, A.; Chesneau, O.; Dominik, C.; Jaffe, W.; Dutrey, A.; Graser, U.; Henning, Th.; De Jong, J.; Köhler, R.; De Koter, A.; Lopez, B.; Malbet, F.; Morel, S.; Paresce, F.; Perrin, G.; Preibisch, Th.; Przygodda, F.; Schöller, M.; Wittkowski, M. (2004). "The building blocks of planets within the 'terrestrial' region of protoplanetary disks". Nature. 432 (7016): 479–82. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..479V. doi:10.1038/nature03088. PMID 15565147. S2CID 4362887.

- Rincon, Paul (5 March 2010). "Probe may have found cosmic dust". BBC.

- Westphal, A. J.; Allen, C.; Bajt, S.; Bastien, R.; Bechtel, H.; Bleuet, P.; Borg, J.; Brenker, F.; Bridges, J.; et al. Analysis of "Midnight" Tracks in the Stardust Interstellar Dust Collector: Possible Discovery of a Contemporary Interstellar Dust Grain (PDF). 41st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference.

- LeBlanc, Cecile (7 April 2011). "Evidence for liquid water on the surface of Comet Wild 2".

- "Stardust Interstellar Dust Particles". JSC, NASA. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007.

- "Stardust@Home - Stardust Search Finding Stardust". foils.ssl.berkeley.edu.

- "Stardust Return Capsule".

- Brownlee, Don (5 February 2014). "The Stardust Mission: Analyzing Samples from the Edge of the Solar System". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 42 (1): 179–205. Bibcode:2014AREPS..42..179B. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-050212-124203.

- Matzel, Jennifer E. P. (23 April 2010). "Constraints on the Formation Age of Cometary Material from the NASA Stardust Mission". Science. 328 (5977): 483–486. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..483M. doi:10.1126/science.1184741. OSTI 980892. PMID 20185683. S2CID 206524630.

- Morbidelli, A.; Chambers, J.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Petit, J. M.; Robert, F.; Valsecchi, G. B.; Cyr, K. E. (February 2010). "Source regions and timescales for the delivery of water to the Earth". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 35 (6): 1309–1320. Bibcode:2000M&PS...35.1309M. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2000.tb01518.x.

- "'Life chemical' detected in comet". BBC News. 18 August 2009.

External links

- Stardust website at NASA.gov

- Stardust website by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Stardust-NExT website by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Stardust Mission Archive at the NASA Planetary Data System, Small Bodies Node

- Stardust-NExT Mission Archive at the NASA Planetary Data System, Small Bodies Node

На других языках

[de] Stardust (Sonde)

Die Raumsonde Stardust (englisch für Sternenstaub) war eine Mission der NASA, die 1999 gestartet und 2011 beendet wurde. Ziel der Mission war das Einfangen von Partikeln aus der Koma des vom Schweizer Astronomen Paul Wild entdeckten Kometen Wild 2 sowie interstellaren Staubs. Die Proben wurden im Januar 2006 zur Erde gebracht. Für die Entwicklung und den Bau der Sonde standen im Rahmen des Discovery-Programms zur Erforschung des Sonnensystems 128,4 Millionen Dollar zur Verfügung, weitere 40 Millionen Dollar wurden für die Missionsdurchführung verwendet. Hinzu kamen Kosten für die Trägerrakete.- [en] Stardust (spacecraft)

[es] Stardust (sonda espacial)

Stardust es una sonda espacial estadounidense interplanetaria lanzada el 7 de febrero de 1999 por la NASA. Su propósito fue investigar la naturaleza del cometa 81P/Wild (o Wild 2) y su coma.[ru] Стардаст (космический аппарат)

«Стардаст» (англ. Stardust — дословно «звёздная пыль») — автоматическая межпланетная станция (АМС) НАСА, предназначенная для исследования кометы 81P/Вильда. Запущена 7 февраля 1999 г.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии